|

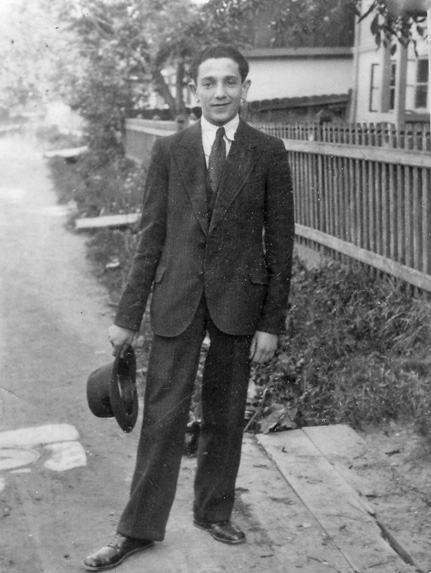

Picture is of Monolo Schreter in Sighet, Romania Mid-1930'S I recently received this lovely piece which tells Historic Facts about the Jews of Sighet.Thank You Shelley Schreter for sharing this piece. Selected Facts on the History of the Jews in Sighet, Maramuresh, Transylvania

Sheldon (Shelly) Schreter, Ra’anana, Israel

Summarized and translated from an encyclopedia of the Jewish communities destroyed in WWII (in Hebrew) published by Yad Vashem in Jerusalem in 1979. The article on Sighet was authored by Yossef Cohen. The joint editors of the volumes on Romania were Jean Ancel and Theodor Lavi. This same article serves as the basis of the text on Jewish Sighet’s history and institutions appearing in the memorial book, “The Heart Remembers: Jewish Sziget”, published in 2003 by the Association of Former Szigetians in Israel. I have borrowed and integrated some of the supplementary material from this second publication in the following summary.

Sighet is on the Tisza River (and its tributary, the Iza River), dividing Romania from the Ukraine, and was the leading town of the province of Maramaros (pronounced “Maramuresh”), in the region called Transylvania, a remote northeastern corner of the Austro-Hungarian empire controlled by the Habsburg monarchy. Commerce in lumber, fruits and other agricultural products were important in its economy. In 1920, most of its population were Hungarians, with a large Romanian minority, while its situation today is exactly the reverse.

The history of the Jews in Sighet goes back about 300 years, and up to 1830 they numbered barely a few hundred. Early documents from the 1700’s and early 1800’s show them working in “traditional” Jewish occupations such as commerce in food, spirits, clothing and textiles, tax-farming, innkeeping and money-lending. They were often targeted by local ruffians, as evidenced by their requests for adequate protection from the local authorities, who evidently did provide it, though not consistently.

Lively economic relations existed between the Jews of Sighet and those of the province of Galicia in Poland, which is where most of them originated.

During the years 1830-1880, Sighet experienced rapid growth from a small village to an important regional center, and its Jewish community flourished in tandem. By 1880, there were over 3,650 Jews there, amounting to a quarter of the population.This trend was to continue and intensify over the next 6 decades, during which Sighet’s Jews grew to over 11,000 in number and as high as 46.5% of the population (in 1920).

The community’s expansion was accompanied by the creation of numerous synagogues and religious organizations and schools, as well as a network of social and charitable institutions to attend to the needy. There are even records of relief activities among Sighet’s Jews in 1891-1900 on behalf of the victims of anti-Semitic persecutions in Russia and Romania.

In 1867, the Hungarian Parliament passed a Statute of Emancipation which granted the Jews the right to participate fully in the economic, cultural and intellectual life of the country, from which they had been restricted up to then. This motivated many Jews to become deeply involved in Hungarian society at all levels, and to espouse strong Hungarian patriotism.

The Jews of Sighet felt comfortable enough in their local status to press the town council in 1889 for permission to erect an “eruv”. This is a wire strung between poles to delineate the area within which it is ritually permissible to carry certain objects on the Sabbath and Jewish holidays. Permission was at first refused, but the Jews of Sighet persisted. Following a 6-year struggle, they finally won the right to their “eruv” in 1895, provided its poles would also serve for electricity lines.

Internal strife and controversy were always present among Sighet’s Jews, as in virtually every other Jewish community, and around many of the same issues: religious organization, including the administration of kashrut; education; competing Jewish ideologies (Zionism, anti-Zionism, etc.); domination of the community by various leading families and Hasidic dynasties; and, in effect, over modernization. Sighet became known for a concentration of Jewish scholarship and great rabbis and yeshivas, including many rabbinical members of the Kahana family, Rabbi Shlomo Leib Tabak (1832-1907) and numerous others. From the mid-19th century through the Shoah, Sighet was dominated by rabbis from the Teitelbaum family dynasty, who succeeded in reinforcing and expanding the Hasidic movement, and whose religious books, responsa and articles earned them illustrious reputations throughout Hungary and beyond.

At the head of Sighet’s “Sephardi” congregation – which was pure Ashkenazi in its membership, but whose brand of religious orthodoxy was regarded as more progressive and enlightened, and which used the Sephardic prayer rite – stood Rabbi Shmuel Benjamin Danzig (1875-1944). He was a graduate of yeshivot in Pressburg and Frankfurt, a highly respected Torah scholar who also had a doctoral degree, active in the religious-Zionist movement, a leader of the Joint Distribution Committee in Sighet, and a member of the Sighet City Council for 30 years.

Education – Up to the end of WWI, the vast majority of Sighet’s Jewish children received a traditional Jewish education in a “heder” or private home, and only a very few of them attended non-Jewish schools. The first Jewish school with a secular curriculum (alongside its Jewish studies) was opened by the Sephardi Congregation shortly before WWI, but its appeal was limited.

Cultural Life – A sophisticated Hebrew printing press was set up in Sighet in 1874, and served as a focal point for publishing activities and cultural life for the next seven decades, until the destruction of the community in 1944. Its output included rabbinical commentaries in Hebrew, a variety of Hebrew and Yiddish periodicals and newspapers, sometimes in a bilingual format together with Hungarian.

Personalities - The vast majority of Sighet’s Jews remained firmly within the community’s framework and had relatively little to do – aside from economic relations – with the non-Jews among whom they lived. Nonetheless, by 1898, Dr. Ya’akov Heller and Attorney Lipot Vadasz from Sighet were elected to the Austro-Hungarian parliament. Other Sighet Jews were nominated to high positions in the civil service, or distinguished themselves in Jewish scholarship (Rabbi Yekutiel Greenwald, 1890-1955). Rabbi Yoel Teitelbaum (1887-1979, also known as Reb Yoelish or the Satmar Rav) was born in Sighet, became the rabbi of Satu-Mare (Satmar), was rescued from the Shoah on the famous “Kastner train”, and went on to become a leading Jewish opponent of Zionism and the State of Israel from his base in New York.

During WWI – Sighet suffered because it was close to the front with the Russian army, which even occupied it for a short time. Many of Sighet’s Jews fled the Czarist army, given its reputation for anti-Semitism. Some Sighet Jews served in the Austro-Hungarian army in the War, including as officers and as medical personnel, and one listing recorded 7 casualties. Even though many of Sighet’s Jews lived a lifestyle rigidly separate from the environment, some of them not even speaking Hungarian, but only Yiddish, more and more of them were becoming involved beyond the confines of the community. When the last Habsburg Emperor, Franz Jozsef, died in 1916, he was deeply mourned by the Jews of Sighet in a patriotic Hungarian spirit.

Between the Two World Wars

Economic and Social Life – The collapse of the Austro-Hungarian monarchy following WWI impacted Sighet powerfully, and not for the better. The province of Maramaros was ceded from Hungary to Romania, and its northern half, north of the Tisza River, became part of the new Czechoslovakian state. Those whose livelihoods were connected to agricultural produce from northern Maramaros were devastated economically. The rapid growth of the Jewish community to that point was halted in its tracks, and a gradual decline began.

In early 1919, during the transition from Hungarian to Romanian sovereignty over the region, anarchy prevailed and there were incidents of personal attacks, property crimes and even murder perpetrated by local thugs and demobilized soldiers against Jews from Sighet and some of the surrounding villages. In response, Sighet Jews elected a civil administration headed by the Zionist leader, Dr. Eliahu Blank (1887-1955), which took charge for several weeks. It organized a civil guard comprised of young Jews with a nationalist consciousness and military experience, which successfully defended the lives and property of the local Jews.

Sighet’s Jews were typically poor, and had large families. Many of them were manual labourers, for example in agriculture and in the local lumber industry, including many lumberjacks. There were also numerous tailors, cobblers, tinsmiths, gold and silversmiths, watchmakers, soap and candle makers, weavers and peddlers. Commerce in local agricultural produce, especially apples, was largely in Jewish hands. The Jewish middle and entrepreneurial class in Sighet was small, and there were only a very few factory and land owners. Most of Sighet’s doctors were – what else? – Jewish.

Institutional Structure of the Jewish Community – By the late 1920s, the community had evolved a stable set of institutions. There was a central communal budget of 4 million Romanian lei, of which 3 million were for social and welfare/charitable functions. Out of 2300 Jewish households, 1895 (82.4%) paid the communal “taxes”! One indication of the level of involvement in Jewish life, or at least of the limits on assimilation, is found in a datum from the 1930 census: 10,450 of Sighet’s 11,075 Jews (94%) listed Yiddish as their mother-tongue.

There were five large synagogues: the Central Synagogue, built in 1836; the Machzike Torah synagogue; the Poalei Tzedek synagogue; the Talmud Torah synagogue; and the elaborate synagogue of the “Sephardi” community, mentioned earlier. There were also 12 batei-midrash, houses of Torah learning, connected with various Hasidic courts such as those of Vizhnitz and Kossov.

The Joint Distribution Committee was active in Transylvania, and particularly in Sighet, following WWI, and concentrated on projects designed to alleviate Jewish poverty and unemployment. Their activities in Sighet included a Jewish orphanage, weaving and carpet workshops, and a co-operative bank.

Rabbinical Personalities – Sighet’s last official rabbi was a scion of the Teitelbaum dynasty, Rabbi Yekutiel Yehuda Teitelbaum (1912-1944). He was named to office while still a minor, indicating the hereditary nature of the post, and three prominent rabbis served as stewards until he came of age: Rabbi Shlomo Dov Heller, Rabbi Meir David Tabak, and Rabbi Yekutiel Yehuda Gross. Following WWI, a number of the rabbinical personalities from the Maramaros region concentrated in Sighet, establishing communities and institutions there. These included Rabbi Pinchas Hager from Borsa, who was a brother of the Vizhnitzer rebbe, Rabbi Yisrael Hager; Rabbi Eliezer Ze’ev Rosenbaum, the Rebbe of Kretschinef; Rabbi Moshe Hager, the Rebbe of Kossov; Rabbi Ya’akov Yissachar Dov Rosenbaum, the Rebbe of Slatina. All of them, except the last-mentioned (and Rabbi Tabak, who died in 1936), were murdered in the Shoah. One last name: a leading follower of Rabbi Hager of Borsa was Shlomo Wiesel, who also died in the Shoah. His son is Elie Wiesel, the well-known author and Sighet’s most famous son.

Education – The attempts to establish Jewish schools covering both Jewish and secular subjects made slow progress, and the great majority of Jewish children continued to receive their education in traditional heders. In the mid-1920s an elementary Jewish school sponsored by the orthodox community and headed by Samu Havas did succeed in attracting several hundred pupils. A small number of children of the local Jewish “intelligentsia” were sent to the local non-Jewish schools. There were never any Jewish secondary schools in Sighet. Families wanting secondary education, including secular subjects, for their children either had to send them outside of Sighet or to frequent the local, non-Jewish high schools (gymnasia).

A fascinating experiment at the central yeshiva of Sighet, with 150 students, was initiated by its director, Rabbi Yekutiel Yehuda Gross. In 1928, he instituted courses in weaving in the framework of the yeshiva, alongside the study of the sacred texts. In the mid-1930s, he expanded these professional courses to agricultural subjects such as poultry-raising, dairy farming and bee-keeping. This was revolutionary in more ways than one, since it was designed to train students intending to emigrate to Israel. In other words, its orientation was explicitly Zionist.

Zionist Activity – The largely anti-Zionist flavour of most Transylvanian Jews and their rabbinical leaders did not prevent the growth of a vigorous Zionist movement in Sighet. Its early leader, Dr. Eliahu Blank, was mentioned in connection with the organization of Jewish self-defense in the turbulent period immediately after WWI. Besides translating Theodor Herzl’s seminal essay, “The Jewish State”, into Hungarian, he had a distinguished career as a Zionist leader, publicist and editor in Maramaros and, after his aliya in 1926, in Palestine/Israel. Another key leader was Rabbi Yossef Lichtenstein (1867-1939) who was a champion and ideologue of Religious Zionism with a special appeal to working-class Jews, arousing consternation and condemnation among his rabbinical colleagues.

A variety of Zionist organizations and youth movements were active in Sighet and Transylvania throughout the 1920s and 30s, and many of their graduates made aliya to Palestine/Israel. While youth movements such as HaNoar HaTsiyoni, HaShomer HaTsa’ir and Beitar did exist, by far the largest movements – given the highly observant character of the region - were the religious Zionist ones (Mizrachi).

In 1919, the Zionist sports organization, “Samson” (Shimshon), was founded, with a particular emphasis on soccer, boxing and gymnastics. Its sporting achievements, especially in soccer, went far beyond local confines and were noticed throughout Romania. Its cultural activities and performances similarly came to the attention of wider audiences. Shimshon’s exploits earned it wide popularity within the Sighet Jewish community, despite the opposition of the anti-Zionist rabbinical leadership. During the mid-1920s, a congress of anti-Semitic students was held, following which its participants attacked Jewish institutions in various parts of Transylvania. Word reached Sighet that a trainload of these students were on their way to town, to repeat the pattern there. A “welcoming committee” was immediately organized, in which Shimshon boxers, weight lifters and other athletes were prominent. Local police took note of the Jews armed with clubs and other weapons, and sent messengers to warn the students at the last train station before Sighet. Prudently, the students disembarked, and never reached Sighet.

A highlight of local Zionist activity was the joint aliya of 70 farmers and their families, totaling 400 people, from Sighet and the surrounding towns in 1935. They departed from the Sighet train station in specially decorated cars, and were seen off by literally thousands of people. Most of them settled in Rechovot.

Another aspect of Sighet’s Zionist activity was a series of publications, in Hungarian, Yiddish and Hebrew, in which numerous young intellectuals took part.

Literary Activity – During the 1930s, Sighet had a number of Yiddish publications which brought young local writers, such as the poet, Yehezkel Ring, to the attention of wider audiences in Eastern Europe. Sighet was also known for a number of significant collections of Jewish books held in several private collections. Its rabbinical luminaries continued turning out noted religious and halachic literature right up to and during WWII. And several important academic scholars of Judaica also came from or studied in Sighet, including Rabbi Mordechai Williger, Prof. David Weiss-Halivni (Jewish Theological Seminary and Columbia U.), and Dr. Naftali Wieder, a noted expert on the Dead Sea scrolls.

Musical Activity – Sighet’s cultural life included a rich musical dimension, with numerous musicians and concerts and musical instruction at high levels. The violin, an instrument which attracted many Jews, was popular in Sighet, and Jozsef Szigeti was its most famous classical violinist. There were also many pianists, as well as masters of other instruments, composers, opera singers, and even jazz musicians. Sighet’s musical life was also enriched by a cadre of talented cantors and composers of liturgical music.

The Shoah

Transylvania was partitioned right at the beginning of the war and returned to Hungary, which occupied Sighet on Sept. 5, 1940. Traditionally, Sighet’s Jews had identified with Hungary, whose culture they perceived to be much more liberal and friendly to the Jews than that of Romania. It was thus shocking when Hungarian sovereignty led quickly to a deterioration in the living conditions of local Jews. Economic restrictions which impoverished many Sighet Jews were soon enacted, and the first arrests and deaths in prison of Jewish merchants were recorded. The first deportations occurred in the summer of 1941, under the guise of “resettling” Jews who were not Hungarian citizens or could not adequately document it. Several hundred Sighet Jews were swept up in this action, and they – together with thousands of other Hungarian Jews – were murdered en masse. In his memoir, Night, Elie Wiesel tells of a lone survivor of this massacre who somehow managed to return to Sighet to tell his tale and to warn his fellow Jews of the fate awaiting them. He was not believed, and was regarded as having gone mad.

During 1941, and at regular intervals through spring, 1944, groups of Sighet men were drafted as slave labour, and not many of them survived the experience. In 1942, various secular leaders of the community were targeted, and arrested on fabricated charges, including Dr. Abraham Fried, a Zionist leader; the merchants Moshe Chaim Jakobovits and Hugo Schongut; Jeno Moldovan, and others.

Throughout 1943 and into 1944, there was a steady stream of Polish Jewish refugees from ghettoes and death camps who reached Sighet via the Carpathian Mountains. They were given shelter and aided in reaching Budapest, where the Zionist organizations had experience in receiving them and arranging for them to go into hiding. Some of Sighet’s leading rabbis – Shmuel Danzig, Yekutiel Teitelbaum and Eliezer Rosenbaum, among others – were actively involved, at great personal risk, in these life-saving activities. Yet, as Elie Wiesel has recorded, the Jews of Sighet, like the Jews in so many other places, continued to believe that the storm would pass them by, and claimed to “not know’ of the Nazis’ Final solution.

On March 19, 1944, Germany officially took control of the Hungarian government, with drastic consequences for Hungarian Jewry, including: confiscation of radios, expropriation of property and bank accounts, barring of Jews from using trains or any other public transportation, and the forced wearing of the yellow star on outer clothing. The Passover holiday that year started on the evening of Friday, April 7th, and ran through Saturday evening, April 15th. Immediately following the holiday, preparations were made for concentrating all of Sighet’s remaining Jews in a ghetto. Some 6,000 Jews from 26 villages in the region were transferred with great cruelty and brutality to Sighet.

Starting on April 20th, some 15,000 Jews were forced into two ghettoes, a larger one occupying 4 streets inside Sighet, and a smaller one in a suburban slum. 140 of the community’s leaders were isolated and imprisoned in a synagogue without food or water, apparently to prevent the organization of any resistance to these measures. Conditions in the Sighet ghetto were typical of those in other ghettoes: gross over-crowding, arbitrary violence on the part of the Hungarian gendarmes, draconian forced labour, etc.

A delegation of the planners of the destruction of Hungarian Jewry, including the Germans, Adolf Eichmann and Dieter Wisliceny, and the Hungarian, Laszlo Endre, visited the ghetto at the end of April, 1944. They wanted to see how the Jews were reacting to their ghettoization, to what extent they realized what was awaiting them, and how the local non-Jewish population was viewing the situation.

During the short time, until mid-May, that Sighet’s Jews lived in the ghetto, they nonetheless attempted to organize their communal life, in the belief and hope that they would stay there until the end of the war. A Jewish Council was appointed, and oversaw various functions, such as the equitable distribution of the little food that was allowed into the ghetto; the organization of the labour battalions demanded daily by the authorities; the maintenance of minimal public health and sanitary conditions, in the radically overcrowded living conditions; the preservation of internal public order, through a Jewish police force; and religious and educational services.

The ghettoes were abruptly cleared and the Jews deported during 4 days in May: the 16th, 18th, 19th and 21st. A little over 3,000 were included in each transport, 12,749 Jews in all. On the way to the deportation trains, each group was led into the central synagogue, where they were systematically robbed of their valuables, body-searched, and subjected to humiliations and vicious beatings. In some groups, the Jews were allowed to take 20 kilograms of possessions with them; in others, one suitcase per person. One group of Jews who tried to hide in a neighbouring forest (Apsa) were captured and executed in the central market square of Sighet. A few individual Jews managed to save themselves by hiding in the homes of their non-Jewish neighbours and friends, even including some police officers, but we have no information as to how many. The implication is clear: extremely few.

From the central synagogue, each group was marched to a special train waiting on a side track, at a distance from the main station. With callous brutality, Hungarian gendarmes squeezed them tightly into the cattle cars, 70 and often as many as 90 to a car. The journey to Auschwitz took 3 days, without a drop of water. At a stop in the town of Kassa (Kosice), any Jews who attempted to approach a water faucet were immediately shot. There were deaths from thirst, typically of infants, in every cattle car.

Very few of Sighet’s Jews survived Auschwitz. The liquidation of the local Jewish community did cause some discomfort in Sighet, for example, in the resultant absence of medical personnel. But for the most part, Sighet’s non-Jews appropriated the property of their former neighbours and just went on with their lives. On July 16, 1944, a Maramaros newspaper exulted in its lead article on the liquidation of Sighet’s Jews, under the heading: “Without Jews.”

After the Shoah

The Red Army occupied Sighet on October 15, 1944. In their retreat, the Hungarian army destroyed the central synagogue of Sighet. During the summer of 1945, the few survivors began returning to Sighet, in search of their families. A figure of 2300 Jews in Sighet in the census of 1947 reflects the fact that survivors from the surrounding region and from places as far away as Bukovina concentrated there for a year or two after the war. Most of them were not original Sighet residents.

The remnants of Sighet’s Jews restored the “Sephardi” synagogue – none of the others could be salvaged, nor was there for whom – and that is the one that was subsequently used on Sabbaths and holidays, and which visitors to Sighet see today. With the help of the Joint Distribution Committee, a modern bathhouse was erected, and next to it, a Mikva or ritual bath. These were later taken over by the municipality. In the immediate post-war era, efforts were made to reconstitute the Sighet Jewish community and its key institutions, in the hope of giving it a long-term future.

During 1946-47, three Yiddish newspapers were published in Sighet, signifying some level of communal and cultural life. This turned out to be short-lived, as the Communist regime established its hold in Romania and quickly made clear its intolerance of any national Jewish movements.

Some Sighet Jews had reached Israel as illegal immigrants during the pre-State period, and participated in the War of Independence. Nine of them were casualties of that war, and even more according to certain sources.

Numerous Sighet Jews emigrated in the early 1950s, to Israel and elsewhere. A second wave departed in 1958, when the Romanian regime eased its pressure on the Zionist movement and permitted aliya to Israel.

In 1977, the community numbered 200 people, with limited activities. Its outstanding figure had been the playwright and author, Y.L. Brukstein, who emigrated to Israel in 1972. Almost all the other post-war community leaders had also by then emigrated or passed away. An organization of former Maramuresh residents was organized in Israel, and was active in the publishing, social, cultural and welfare areas. OR |